Intent To Use – Weekly Newsletter Brought to You By Garbis Law, LLC

Dear Reader:

The big news out of Gotham last week was that the Batmobile took down another imposter and added some copyright protection to its arsenal.

A case was brought before the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit which put DC Comics, the rights holder to the Batman series, against Mark Towle, an individual who created replica Batmobiles.

The main issue here was whether or not the Batmobile was a character and therefore entitled to copyright protection.

Background Info:

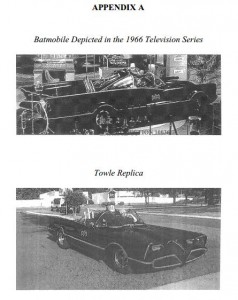

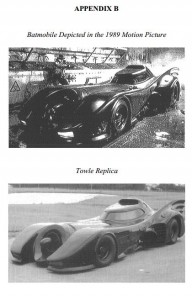

Mark Towle, the defendant in this case, decided to make and sell replicas of the Batmobile, as seen in the 1966 television series and the 1989 movie. Towle sold these replicas to “avid car collectors” for a whopping $90,000 each. If you didn’t want to buy the whole car, there was no need to worry because Towle would also sell kits to make your car look like the Batmobile.

Take a look at these images from the lawsuit showing each Batmobile:

As you might expect, DC Comics wasn’t a fan of this and sued Towle for copyright infringement, trademark infringement, and unfair competition. We’ll only be looking at the copyright issue, mainly because the trademark infringement is fairly obvious here, as Towle openly used the “Batmobile” name to market his products and business. Even his website was named Batmobilereplicas.com, which has now been shutdown…sorry for those who wanted to spend some of that extra money on a custom Batmobile!

Towle’s defenses to the copyright infringement claim were:

- The Batmobile was not subject to copyright protection; and

- DC Comics did not own the copyright in the Batmobile as it appeared in either production.

Is the Batmobile Entitled to Copyright Protection?

The Court, through prior decisions and analysis, has developed a three part test to determine whether or not a character in a comic book, television program, or motion picture is entitled to copyright protection:

- The character must generally have physical as well as conceptual qualities;

- The character must be “sufficiently delineated” to be recognizable as the same character whenever it appears; and

- The character must be “especially distinctive” and “contain some unique elements of expression.”

After applying this test, the court found that the Batmobile was entitled to copyright protection.

The Batmobile has appeared graphically in comic books, and as a real car in movies, therefore it has “physical as well as conceptual qualities.”

To be “sufficiently delineated,” a character must display consistent, identifiable character traits and attributes. Here, the court reasoned that throughout the years, the Batmobile displayed similar character traits and attributes, even if the physical appearance changed. Regardless of the look, the Batmobile was always a highly modified vehicle with lots of weapons, power, and attitude. There was no mistaking which vehicle was the Batmobile in any Batman movie, tv series, or comic, therefore the second requirement of the test was met.

The third prong is satisfied because the Batmobile is not merely a stock character. It has a unique and highly recognizable name, in addition to all of its character and physical traits.

Towle attacked the second part of the test and argued that the Batmobile had appeared without its “bat-like” features at times. This argument didn’t gain any traction, however, as the court was able to show other examples of characters who may have changed in appearance, but were still viewed as the same. For example, the Court found that Eleanor, a car in both the original 1971 and 2000 remake motion picture Gone in 60 Seconds, met all the necessary factors to qualify for copyright protection. This was the case even though in the original movie it was a yellow 1971 Fastback Ford Mustang, and in the remake it was a silver 1967 Shelby GT-500. The essence of the character wasn’t the actual car, but rather the trouble it would give the human characters trying to steal Eleanor in both movies. The same can be said for characters like James Bond and Godzilla. Even though the appearance may change, the overall character remains very similar. The Batmobile, is therefore not just a vehicle or prop, but a character in these comics and movies.

Does DC Comics Own the Copyright?

Towle then goes on to argue that DC Comics didn’t actually own the copyright in the 1966 TV series and the 1989 movie.

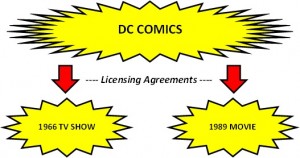

To better understand Towle’s arguments, I created a sweet graphic to break down the two separate licensing agreements we find in this case.

DC Comics entered into licensing agreements with ABC for the 1966 TV series and Batman Productions, Inc. for the 1989 movie. There’s no question that DC Comics owns the original copyright to the Batman series, and even the original Batmobile, but Towle’s argues that because DC licensed it out to others and gave them permission to create their own take on the Batmobile, the copyrights are not owned by DC.

Towle’s, however, fails to consider the role of “derivative works” in copyright law. A derivative work is made by using the original, and a copyright owner has the right to create a derivative work or to authorize others to do so.

According to the Court:“when a copyright owner authorizes a third party to prepare a derivative work, the owner of the underlying work retains a copyright in that derivative work with respect to all of the elements that the derivative creator drew from the underlying work and employed in the derivative work.”

In other words, someone who copies a derivative work without authorization will be infringing on the original owner’s copyright, as is the case here. It didn’t matter that DC Comics authorized others to create derivative works; it still retains the right to sue any parties who are infringing on its copyright.

That’s all for now…back to the Batcave!