This week’s newsletter was inspired by a story I read on the San Antonio Express News (“SA Express”) website about a fan of the NFL’s Oakland Raiders who recently applied for the trademark SAN ANTONIO RAIDERS.

Along with the news that the St. Louis Rams will be moving to Los Angeles next year, there have been rumblings and rumors that San Antonio might be a potential destination for the Oakland Raiders.

According to the SA Express, Lane Blue, the Raiders fan who applied for the mark, claims his “whole intent is to block the Raiders from moving to San Antonio.” Blue states, “I figured if I took over the name, San Antonio Raiders, I could force the team to stay in Oakland. Now I own the name, so they can’t move there.”

That’s a nice thought, but would that actually work? It’s fairly common for individuals to apply for marks they have no intention to use, but hope to gain something from those applications…usually money from a third party.

It’s not that simple though.

How many times have you read a document and you just “check the box” to get to the next step without actually reading it closely? It’s ok, we are all guilty of it. I didn’t really start paying closer attention to them until I was in law school, so I can’t blame you.

In this case, Mr. Blue forgot to read the fine print. You should always think twice before simply checking the box for an intent to use trademark application.

BREAKING DOWN THE BONA FIDE INTENT TO USE REQUIREMENT

At the end of the each trademark application, there is the following section you must agree to:

The signatory believes that:

if the applicant filed an application under 15 U.S.C. § 1051(b), § 1126(d), and/or § 1126(e), the applicant has a bona fide intention, and is entitled, to use the mark in commerce on or in connection with the goods/services in the application. The signatory believes that to the best of the signatory’s knowledge and belief, no other persons, except, if applicable, concurrent users, have the right to use the mark in commerce, either in the identical form or in such near resemblance as to be likely, when used on or in connection with the goods/services of such other persons, to cause confusion or mistake, or to deceive. The signatory being warned that willful false statements and the like are punishable by fine or imprisonment, or both, under 18 U.S.C. § 1001, and that such willful false statements and the like may jeopardize the validity of the application or any registration resulting therefrom, declares that all statements made of his/her own knowledge are true and all statements made on information and belief are believed to be true.

The bolded portion of that statement calls for a “bona fide intent” to use the mark. In the 2015 case of M.Z. Berger & Co. V. Swatch AG, the Federal Circuit affirmed a Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) decision in which it was ruled that the applicant failed to prove that he had a “bona fide” intent to use the mark in commerce at the time he filed the application. In that case, Berger filed an intent to use application for the term IWATCH, which was opposed by Swatch. Part of Swatch’s opposition was based on what it felt was a lack of intent to use the mark in commerce by Berger.

After concluding that lack of bona fide intent is proper statutory grounds on which to challenge a trademark application, the Court went on to define the meaning of “bona fide intent.” Section 1(b) of the Lanham Act, which governs trademark law, states:

A person who has a bona fide intention, under circumstances showing the good faith of such person, to use a trademark in commerce may request registration of its trademark on the principal register hereby established by paying the prescribed fee and filing in the Patent and Trademark Office an application and a verified statement, in such form as may be prescribed by the Director.

The Court concludes that although there isn’t a specific definition of “bona fide intent,” the reference to “circumstances showing the good faith” strongly suggests that the applicant’s intent must be “demonstrable and more than a mere subjective belief.” This is important as it requires an applicant to objective evidence as to the intent to use the mark. The Court notes that the evidentiary bar is not set really high, but it should be able to show that the “applicant’s intent to use the mark was firm and not merely intent to reserve a right in the mark.”

As you can see, you shouldn’t apply for a trademark if you have no intent to use it.

Getting interviewed by your local newspaper and stating your false intentions doesn’t help the situation either.

It is likely this application will receive an opposition and proving that the applicant has no “bona fide intent” to use the mark in commerce shouldn’t be too difficult.

Remember…read the fine print!

WEEKLY PATENTS:

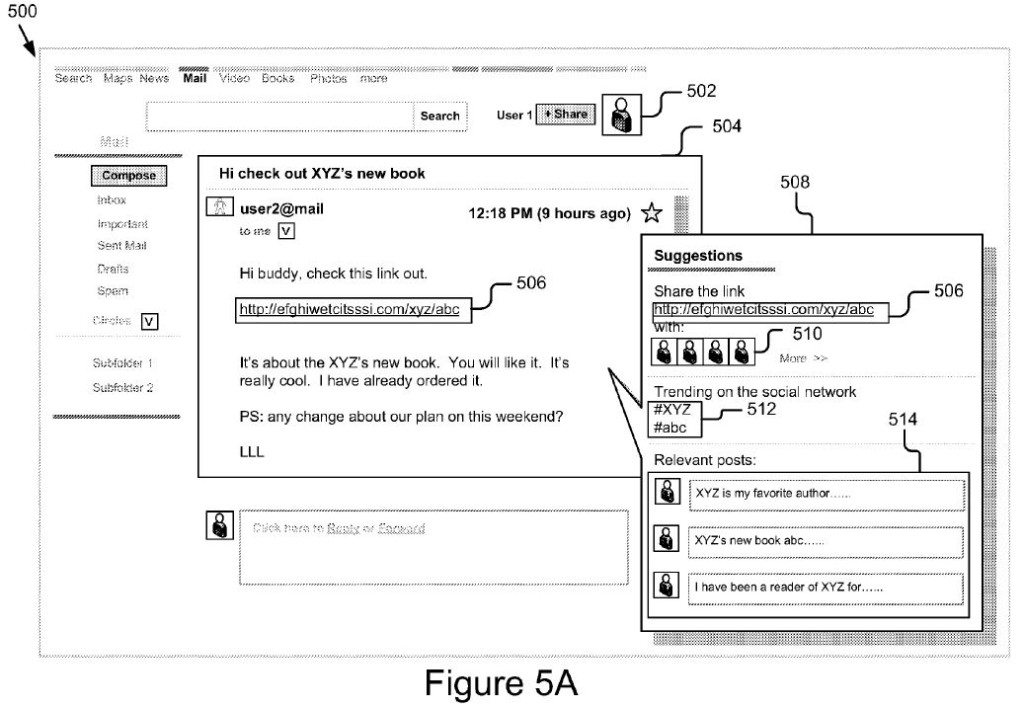

GOOGLE GETS SOCIAL MEDIA PATENT

On January 19, Google received a patent for “Encouraging Conversation In a Social Network.” This covers a system and method for recommending social activity and social conversation to a user. The system can provide an easy way for a user to start a social conversation through email. In one example, it would provide access to various social networks by sending or receiving an email. The system would then determine other users you would like to share a conversation with and identify a topic associated with your email to share to those users. It would utilize a compilation of data to determine what language and topics would result in increased engagement by secondary users.