Have you seen those bumper stickers or license plate frames on cars that say “my other car is a _________(insert luxury brand)?” You can usually find them on in-expensive cars that have seen better days right? If you find those funny, then I have some good news for you…

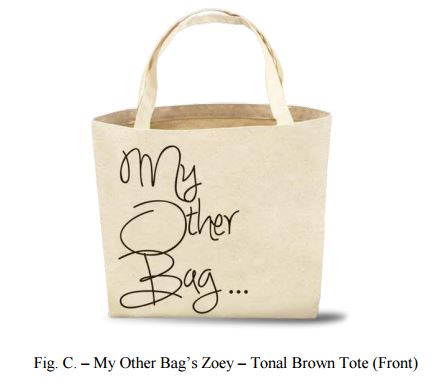

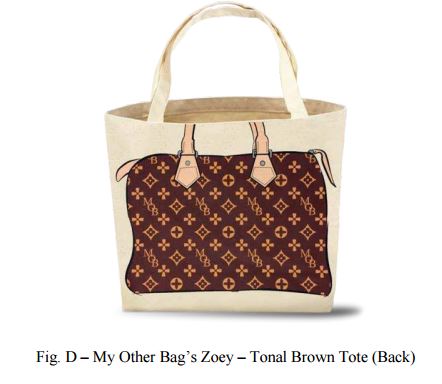

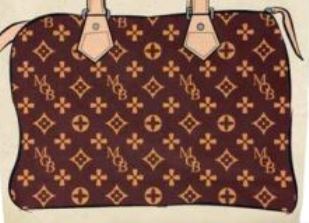

The defendant in this case, My Other Bag, Inc. (“MOB”) sells canvas tote bags that are essentially a play off of those bumper stickers. On one side of the bag is the company’s name “My Other Bag” in a stylized font. On the other side is a drawing of an iconic (and expensive) handbag by luxury designers. In this case, that design was of a Louis Vuitton bag as seen below:

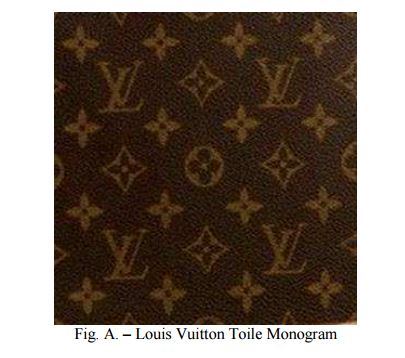

As I’m sure most of you know, Louis Vuitton is a world-renowned luxury brand which often sells handbags for thousands of dollars. MOB, on the other hand, was founded in 2011 and its bags are sold for anywhere between $35 and $55. MOB remains consistent throughout its products, as all of its bags display a caricature of an iconic bag on the one side. In this case, MOB replaces the interlocking “LV” found on the Louis Vuitton bag’s pattern with an interlocking “MOB” instead:

Louis Vuitton didn’t appreciate the joke, so it brought forth three claims against MOB:

- Trademark dilution;

- Trademark infringement; and

- Copyright infringement.

What is Trademark Dilution?

Trademark dilution is the weakening of a famous mark’s ability to identify and distinguish goods or services. Louis Vuitton is asserting dilution by blurring, which occurs when “the unauthorized use of a famous mark reduces the public’s perception that the mark signifies something unique, singular, or particular.”

The court in this case provides examples of your typical dilution by blurring cases as it usually involves using a famous mark to sell unrelated products, such as “Dupont shoes, Buick aspirin tablets, Schlitz varnish, Kodak pianos, Bulova gowns, and so forth.”

Proving dilution under federal law is a two step process. First, a plaintiff must show that the trademark is truly distinctive or has acquired secondary meaning. Second, it must be proven that there is a likelihood of dilution as a result of blurring. There is a six factor test the court should apply to assess whether dilution by blurring is likely to occur. In this case, however, there is a significant exception provided by federal law that states when used in a parody, the use of the famous mark shall not be actionable as dilution by blurring.

A previous case involving Louis Vuitton was cited by the Court to help define a “parody” as “a simple form of entertainment conveyed by juxtaposing the irreverent representation of the trademark with the idealized image created by the mark’s owner.” Louis Vuitton Malletier S.A. v. Haute Diggity Dog, LLC, 507 F.3d 252, 260 (4th Cir. 2007) (“Haute Diggity Dog”).

A successful parody must show a consumer that the defendant is in no way connected to the owner of the trademark it is making fun of.

The court begins by addressing the fair use defense relied on by MOB:

To establish fair use, the Court reasoned that the play off of the well-known “my other car…” joke, and the cartoonish renderings of the Louis Vuitton’s bags, “builds significant distance between MOB’s inexpensive workhorse totes and the expensive handbags they are meant to evoke, and invites an amusing comparison between MOB and the luxury status of Louis Vuitton.”

The Court also compared this case to a previous Louis Vuitton case against Hyundai Motor. In that case, Hyundai aired a “Luxury” commercial to advertise one of its vehicles. In a small portion of that commercial, a scene of a basketball game was shown, where the actual basketball evoked the Louis Vuitton brand as shown below:

The Court in that case rejected the parody defense, as there was no intention by Hyundai to make any statements regarding Louis Vuitton. A parody defense requires you to address the actual brand you are making fun of, while not confusing consumers of your association.

The Court in this case also cites a previous Tommy Hilfiger case in which it was explained that:

“Trademark parodies . . . do convey a message. The message may be simply that business and product images need not always be taken too seriously; a trademark parody reminds us that we are free to laugh at the images and associations linked with the mark.”

In order for MOB to be successful in its parody and to actually make its point, it needs to depict a luxurious handbag on the one side of its inexpensive totes or else nobody would get the joke.

With all of that said, the Court found that MOB can use the fair use defense here.

As to the dilution by blurring claim Louis Vuitton makes, the Court quickly dismissed it, as Louis Vuitton’s fame and recognition “only make it less likely that MOB’s use would impair the distinctiveness of Louis Vuitton’s marks.” MOB did enough to distance itself from Louis Vuitton to avoid a claim of trademark dilution.

Trademark Infringement –

Addressing Louis Vuitton’s second claim of trademark infringement, the Court needs to determine whether or not there is any likelihood that ordinary purchases of the bags would likely be misled or confused as to the source of the goods.

To determine this, courts apply an 8-factor test comparing the marks in question. Those factors are:

- Strength of the trademark;

- Similarity of the marks;

- How related the products are and whether or not they compete with each other;

- Whether or not the senior user of the mark would “bridge the gap” and enter the same market as the infringer’s product;

- Actual consumer confusion;

- Bad faith by allege infringer of adopting the mark;

- Quality of the products; and

- Sophistication of consumers in the relevant market

The Court in this case goes through and analyzes each factor, but as it addresses when dealing with parodies, normal application of this test is “at best awkward in the context of parody, which must evoke the original and constitutes artistic expression.”

Usually, when dealing with a likelihood of confusion, the stronger the mark, the more likely it is that the alleged infringer is using it to increase its commercial presence. In parodies, however, it works the opposite way. When the mark is really strong, as is the case here, it’s much more likely that the audience realizes it’s a joke leading to finding of a valid parody and no likelihood of confusion.

Louis Vuitton tried to argue that its handbags are directly competitive, but the Court wasn’t buying it.

Shocking.

After analyzing all of the factors, the Court finds that purchasers would not be confused when buying these bags. Nobody will be thinking they just purchased a Louis Vuitton bag because it is depicted as a cartoon on the side of a tote bag…at least you would hope not!

As the Court states, in some cases it is better to “accept the implied compliment in a parody” and to smile or laugh than it is to sue. Tommy Hilfiger, 221 F. Supp. 2d at 412.